Approaching Goryudake, July 2013 (photo: Joseph Mecha)

Surprise! In the latest in a series of flip flops, we've decided to extend what was once a three part guide (later a four part guide) into a five part guide. This week, we present the most critical topic of all.

In addition to personal experience and the treasured fellowship of proper mountaineers, I've found myself relying on a now archived feature by SHK alum, Michael Barbic. You can read Mr. Barbic's piece by linking to our site's comprehensive guide to trekking and scrolling about 2/3 of the way down the page.

Part IV: Safety

Mountain safety is a major topic demanding careful consideration. As you gain experience on mountain trails, your awareness of the dangers you face and how to minimize those dangers will develop naturally. But first you have to reach that point safely. Back when I was getting started out, a group of my friends and I found ourselves well beyond our comfort levels when crossing the Karasawa Traverse en route to Okuhotaka. This part of our trek presented unfamiliar hazards like an exposed knife-edge ridge, sections of nearly vertical scrambling, and in one case a big falling rock that nearly did for all three of us. Scary stuff to be sure, but it was that experience that armed us with the confidence and mental fortitude to take on Tsurugidake a month later.

As with driving a motor vehicle, those early brushes with danger that suffuse you with a healthy sense of fear are the best teachers out there. But again, you must survive those brushes...

Since I began writing for this site back in 2012, I've heard accounts of spectacularly ill-advised behavior: a group of Japanese uni students conducting their descent from Yari to Kamikochi entirely in the dark; a pair of Americans trying to navigate snow walls along the Karasawa Col with naught but tennis shoes on their feet; a group of golden oldies starting their ascent of Mt. Jonen in late afternoon. And the list goes on.

Here, in brief are a few nuggets of common sense to start you on your journey.

Research

Most print resources on hiking in Japan are Japanese language tomes like these ones.

Embarking on a mountain excursion without knowing exactly where you're going or how to get there is not a good look. Ideally, you will want to consult both printed and online resources before beginning your trek. And as luck would have it, we posted a feature on this very topic last week. Get a good guidebook or three and review the maps thoroughly. An easy to carry volume that you can whip out on the trail to consult is always a good idea. Even if you don't read Japanese, it's often worth having a look at a site like Yamareco for the maps and pictures posted there by users. A little poking around online will also reveal valuable firsthand accounts like those that make up Wes Lang's Hiking in Japan.

Knowing Your Limits

Another anchorite another dawn. Sunrise near the Goryu Sansou (summer, 2013)

This point is simpler in principal that in practice. Even seasoned veterans occasionally underestimate the difficulty posed by certain treks. As a general rule though, you should start with modest treks and work your way up to more challenging ones. Along with first hand accounts, some of the best references for level of difficulty are official online guides like this one for Nagano and this one for Yamanashi.

Topping the list of Nagano's most technically demanding areas is the Daikiretto. The Hotakadake Traverse, which includes a perilous stretch between Mount Okuhotaka and Nishihotaka is not far behind. Every year, local authorities record dozens of fatal accidents which may have resulted from little more that a brief lapse in concentration. At time of writing, official statistics reveal that just over half of the trekking emergencies (and nearly half of the fatalities) in Japan's mountain ranges this year occurred in the Northern Japan Alps.

Gearing Up

Specialty gear like winter boots and heavy crampons, while not always necessary, can be indispensable in certain situations.

Bringing the gear you need and leaving the gear you don't is another example of mountaineering "common sense" that takes a while to cultivate. You won't be needing an ice ax or crampons to hike Yatsugatake in August for the simple reason that there's no snow there in summer. On the other hand, if you're planning a glacier walk up Shirouma at the same time of year, you'll definitely need crampons. Helmets are another interesting case. You often won't need one, but if you're ridge walking or scrambling then a sturdy, death-resistant plastic dome around your skull could save your life. Research your route and plan accordingly.

Here, in order of importance are a few items which are essential to any mountain excursion:

- Appropriate clothing and footwear. Hiking boots in particular top the list.

- A backpack. Preferably one with a water resistant shell you can cover it with.

- Water. Don't leave home without it.

- Food supplies. What the Japanese call 行動食 (koudoushoku), high calorie snacks like rice balls and trail mix will fend off hunger and help replenish your energy.

- Rainwear. A rainproof shell will help you avoid getting soaked (and possibly very cold) in the event of a sudden downpour.

- Ziplock bags. Large or small, these are great for keeping things dry.

- Any special gear you need, including crampons, an ice ax, headlamp, gaiters, snowshoes, etc. There are times when you can't get where you're going without the necessary tools.

Beyond these items, we start to get into survival tools such as knives, matches, first aid kits, etc. If you are used to carrying a knife--which most would agree is an essential hiking tool--please be aware that Japan has strict laws regulating what kind of knife you can carry. Staying on the right side of these laws can save you a lot of trouble.

Time

Awareness and management of time are both fundamental to mountain safety. First, you need to appreciate the importance of starting and finishing your hike as soon as possible. Showing up at a mountain hut past dark will at best get you scowled at and at worst get you turned away. OK, probably not turned away, but it's still very poor form. It's also important to give yourself some leeway with how you budget time. I've certainly had the experience of a hike taking much longer than a guidebook said it would. One countermeasure to this is to consult multiple sources regarding things like time and level of difficulty.

Weather and Trail Conditions

Soaked but not unbowed on the Hachimine Kiretto, July 2013 (photo: Joseph Mecha)

Another common sense precaution that too often gets neglected is checking the weather and adjusting your plans accordingly. This is especially true of late autumn and early spring when snowfall can pose a major threat to your safety. Rain is less of a threat, but thunderstorms are deadly serious in the mountains. Essentially, if you hear thunder, you should consider yourself in danger of being struck--hence the old adage, "When the thunder roars, get indoors." But what if you're miles from shelter on an exposed ridge? We recommend cancelling your plans to avoid inclement and potentially dangerous weather if it is expected. Mountain huts around Japan post updates for 登山情報 (info on trekking conditions) on their home pages. Feel free to hit us up on our Facebook page if you have any questions about this.

Customary Precautions

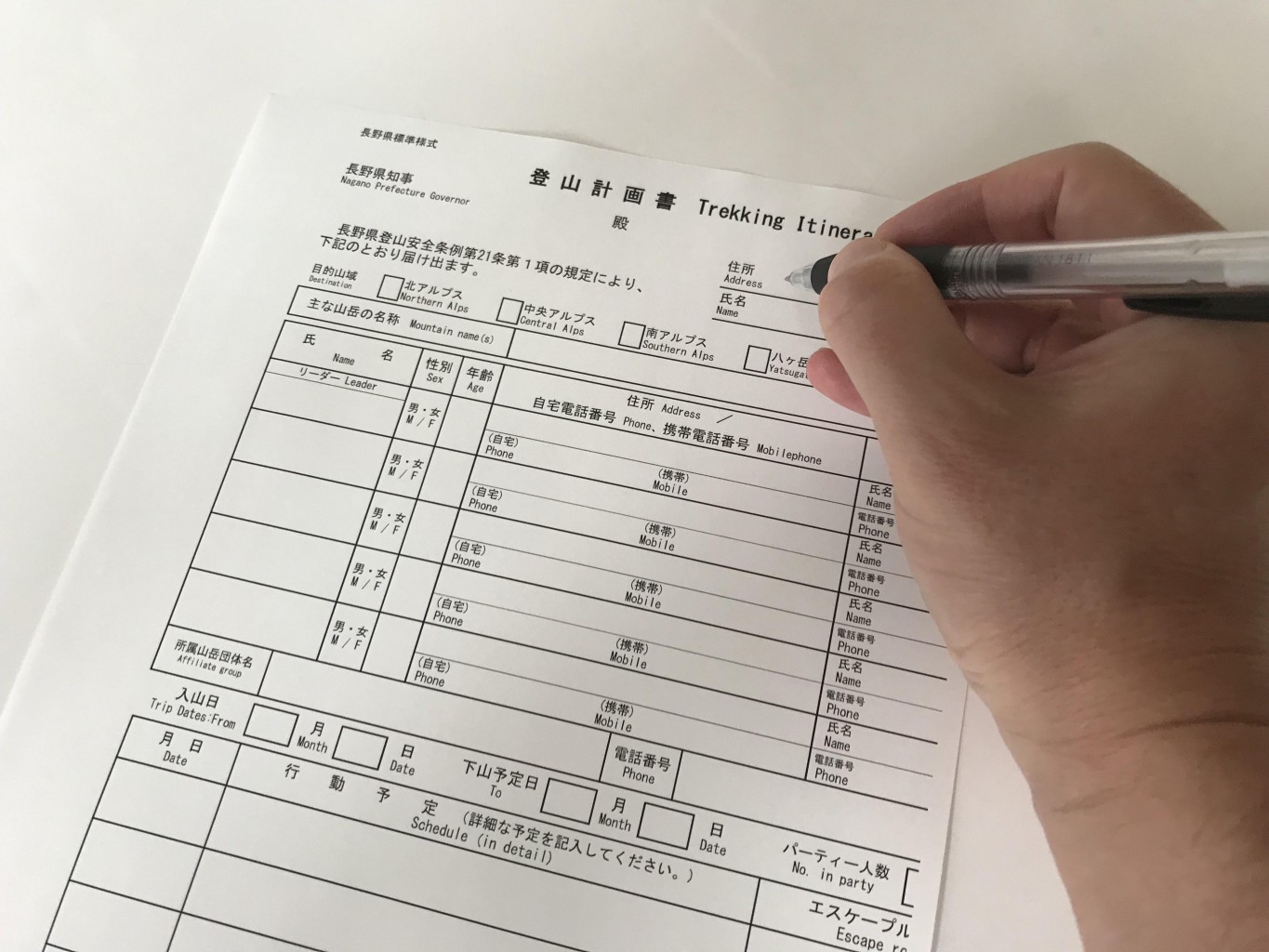

A trekking itinerary like this one could save your life.

Before embarking on a mountain excursion in Japan, you are required to submit an itinerary called a tozan keikaku (登山計画) to local authorities. If you're hiking around Kamikochi, this will be the Matsumoto Police Department. You can download and print a PDF file of the form here. Obviously, you don't need to submit a form for a leisurely daytime walk to Myojin Pond. For a multi-day trek, though, it's a must. To put this in perspective, a large majority of people involved in trekking emergencies this year made it out in one piece, often thanks to the timely intervention of rescue personnel. Their job is in turn made much easier by knowledge of where beleaguered hikers were heading.

Before concluding this part of the guide, I'd like to share one final piece of wisdom which was imparted to me by a veteran mountaineer in a hut atop Harinoki one night over glasses of snow chilled sake: "Sometimes, it takes more courage to turn back than to keep pushing on." There are times when ego or ambition can eclipse our concern for our own safety, but even the brave men and women who serve in the police department's rescue teams live by the creed of preserving their own lives while saving others.

Stay safe!