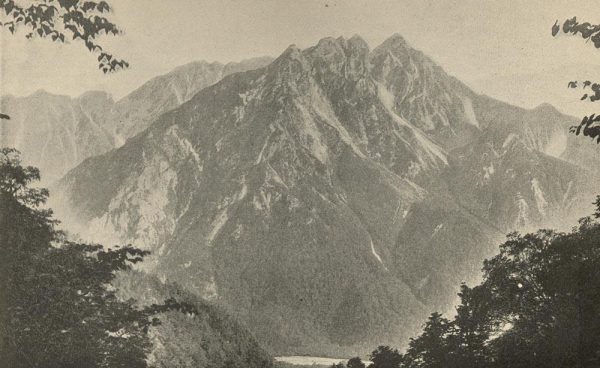

Myojindake as photographed by H.J. Hamilton (photo: http://www.baxleystamps.com/litho/weston_1896.shtml)

Yarigatake, Norikura, Hotakadake, Shirahone Onsen, Hirayu: names familiar to anyone who has taken the time to explore in and around Kamikochi. Generations of visitors to the Japanese Alps have passed through these storied locations. Among the first to sing their praises, however, was a redoubtable clergyman from Derbyshire named Walter Weston.

In the 1890s, Rev. Weston undertook multiple sorties into the mountains of central Japan, recording his experiences in a 300 page volume called, “Mountaineering and Exploration in the Japan Alps.” He belonged to a different generation of explorers with a more limited tool set, but made up for this with a robust appetite for lofty peaks and mountain vistas. For the modern reader with a knowledge of Japan’s alpine ranges and their surroundings, the book is a fascinating document. It is at once familiar and utterly foreign in its presentation of well-known places as they were once and will never be again.

Early on in his travels, Weston and a friend (one of a rotating cast of travelling companions), travel by rickshaw from Karuizawa to Matsumoto. Weston’s goal is to conquer Mt. Yarigatake. His first sortie takes him through what is now Kamikochi, via Hashiba and Shinjima. Along the way, we get early glimpses at Weston’s interactions with the locals. These range from courteous, if rustic, innkeepers to hunters who seem to bestride rural, alpine settlements on one hand and the untamed wilderness on the other.

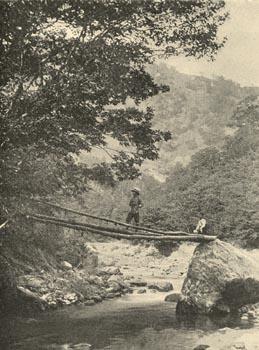

"Pole bridge at Abo Pass" as photographed by T.J. Hamilton (photo: http://www.baxleystamps.com/litho/weston_1896.shtml)

Weston’s descriptions of these folks sometimes betray the prejudices of his age. At an inn, he remonstrates the noisy revelers in the adjoining room for “childish” behavior and often refers to the guides he engages as his “coolies.” The latter can rankle somewhat, given how much Weston relies on guides to carry his luggage and perform other toilsome tasks involved in his ascents. If he sometimes speaks with an air of lordly pomp, however, Weston also presents himself as a kindly figure. He praises courtesy wherever he finds it and doles out the latest 19th century medicine to sickly people in remote areas, while also taking an ecumenical view of Buddhism that seems progressive for the time.

The "Thunder God" at the Mausoleum of Iemitsu at Nikko" (photo: https://www.kamikochi.org/history/the-oldest-hut-in-kamikochi)

Weston’s first attempt at Yarigatake ends in failure as dangerous conditions and insufficient time force his party into retreat. Vowing “revenge,” he travels south to the port town of Kobe traversing parts of the Nakasendo and riding the rapids of the Tenryugawa river in a small wooden boat.

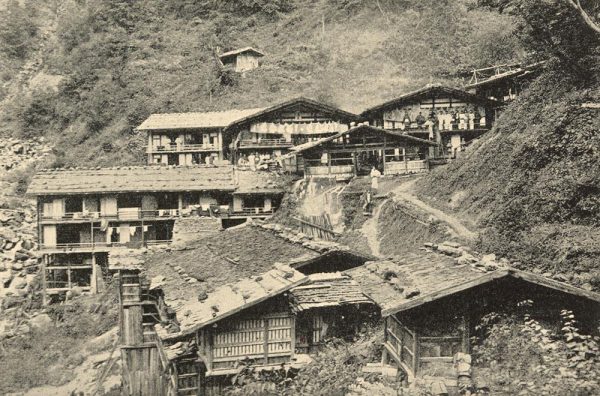

The following year finds Weston and a new companion returning to the area, this time from the Gifu side. En route to Yari, he takes the waters at Shirahone Onsen, a place which has changed profoundly in the intervening years. The photographs which supplement the text greatly enhance its evocative power.:

"Bathhouses of Shirahone Onsen at the foot of Norikura." (photo: T. Hori, http://www.baxleystamps.com/litho/weston_1896.shtml)

Having failed in his initial attempt to climb Yari, Weston twice revisits Kamikochi, the first time to realize his most cherished goal of ascending "the spear mountain." On finally reaching the summit, a clearly exultant Weston describes his surroundings:

The actual summit is a small platform a few yards long, dropping on the east and west in perpendicular cliffs, and affording a prospect grand and impressive in the extreme. To the north stretches the long line of rugged peaks that separates the province of Etchu from parts of Echigo and Shinshu. The wild valleys that radiate from their bases are very little known, excepting to an occasional hunter of chamois, boar, and bear. (MaEitJA, pp. 93-4).

"Yarigatake from the NE." (photo: T. Hori, http://www.baxleystamps.com/litho/weston_1896.shtml)

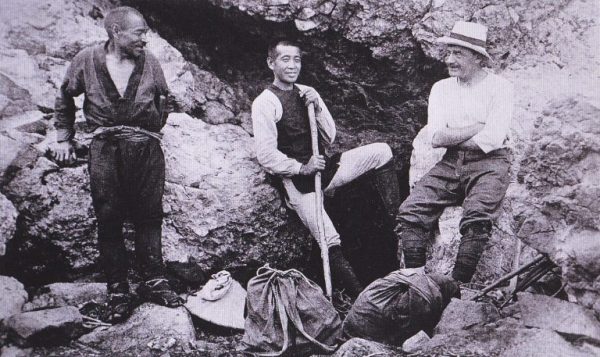

Weston's third trip to Kamikochi sees him enlist the services of the guide Kamonji for an excursion to the peak of Hotakadake (which Weston calls Hodakayama). Kamonji is something of a legend in Kamikochi as the historic hunter and trailblazer whose humble lakeside hut would one day become the Kamonjiya-goya lodge in the Myojin area.

Reading Weston's account of his own interactions with Kamonji, I was surprised to discover how fractious their relationship was at times. Whereas Weston was used to more compliant guides and porters, Kamonji clearly followed his own agenda, sometimes squabbling with his employer about taking unnecessary risks. Toward the end of the excursion, Weston and Kamonji blunder into a literal hornet's nest, providing the book's standout moment of physical comedy. It's one of the few times the normally unflappable Weston is made to pay for his exuberant lack of caution.

Weston and two guides. (Kamonji is on the left).

The remainder of the book takes Weston through a series of adventures throughout the Japan Alps before finally bidding the area farewell in the closing chapter.

In summary, I greatly enjoyed Weston's account of his travels in the mountains of 19th century Japan. The narrative includes many areas I recognized from my time hiking and climbing my way around Nagano over the past decade or so including the town (now city) of Omachi where I lived for five years. Anyone with even a passing interest in the Northern Alps and their history as well as the early days of recreational hiking in Japan should definitely give "Mountaineering and Exploration" a read. You can find it in various printed editions as well as in a number of free online texts, such as this one.

Sources of Information:

Archive.org's online text of Weston's "Mountaineering and Exploration in the Japan Alps: https://archive.org/details/mountaineeringex00westrich

Baxley Stamps photo gallery: http://www.baxleystamps.com/litho/weston_1896.shtml

An archived article from our homepage: https://www.kamikochi.org/history/the-oldest-hut-in-kamikochi

A survey of Northern Alps history, including Weston, also from our homepage: https://www.kamikochi.org/history/a-beginners-guide-to-the-northern-japan-alps-part-1

...